People often ask me how I, a trained scientist, became an author—after all, doesn’t a person go through the process of acquiring a PhD so they can teach and/or research at a university? In my case, the answer was “No.” My goal was to get as much higher education as possible so that I’d have the credentials to be taken seriously as a scientist. I felt that piece of paper would give me “cred” in the academic world and give me choices. My dad was a PhD/MD, so I had a family role model for becoming well-educated. The MD part wasn’t on my radar, but the PhD part definitely was.

Fast forward to 1970. I’d married fellow student Greg Patent; we’d received our doctorates, produced two sons, and spent two years at different postdoc sites. We’d settled in Greenville, N.C., for his new job as a zoology prof. I was at home with the boys, wanting to “do something” with my education, but what? What could I do in this small town, with a Ph.D. and two young boys? I wanted to stay at home, but I didn’t want to be a “stay-at-home mom.”

I went through a logical mental process. I loved books—my favorite gift always being a book on butterflies or frogs. My studies had involved a lot of writing, and my teachers were happy to use their red pens to point out any flaws in my prose. I enjoyed the writing process and learned a lot about good writing from those profs. My boys enjoyed hearing me read life history books about animals. How about writing those books myself?

I had no knowledge of the publishing industry, and like so many other writers, I didn’t check out the business side of the business. I made typical errors—my first story was about an anthopomorphic tadpole named Tommy, who couldn’t understand the changes happening in his body as he turned into a frog. And I even did some drawings as illustrations. Talking animals and amateur art? WRONG!!

Next was a life cycle story about bumble bees, based on the kind of books I read to my kids. I sent the story to one of the life cycle books publishers, Holiday House. This was the RIGHT decision! The publisher wasn’t doing any more life cycle books, but the editor—appropriately named Ed—liked my writing. Whew! I was going to be an author, and I’d found my publishing home. My strategy was proven correct by this note in his letter to me:

“I’m always glad to hear of any PhD. in any area of the life sciences who wants to write for young people, since the likelihood of accurate, unsentimentalized mss is higher. Thanks for writing.”

Bit by bit, Ed educated me about the business as he rejected my ideas. Then, just as we moved to Missoula in 1972, for Greg’s new job at the University of Montana, Ed sent me a challenge. Holiday House wanted a book about the weasel family, the Mustelids. Was I interested in writing an outline and sample chapter to be considered for the project?

Of course I was! I spent much of my first summer in Montana in the university library, learning about this varied and fascinating animal family and writing the sample material. Off it went to Ed, and soon he got back with a contract! My career began.

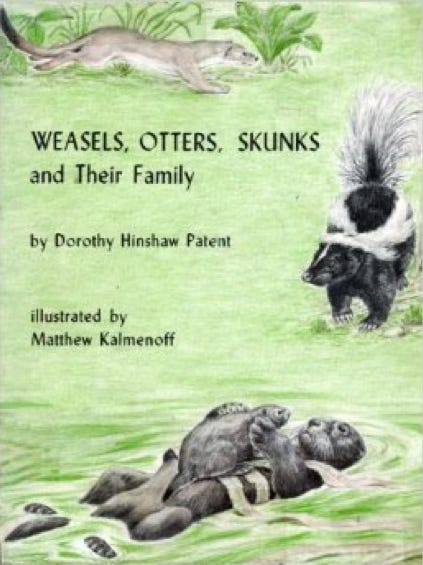

Here’s the result, published in 1973. Back then, books in full color were very expensive to produce and hence very rare. Just having one color on the jacket was special!

I see posts on LinkedIn from folks who are bemoaning the fact that they can't find a field in their specific degree field after they graduate with degrees. One lady went to far as say that she wouldn't accept a job that was offered to her because they didn't have the specific equipment she trained on.

And, here you are, a PhD, who made creative use of your degree ... to the benefit of countless children. So much for the idea of the stuffy, arrogant PhD!

Lovely story Dorothy. Hope other young women scientists will be inspired to have a go!